M-x apropos Emacs

Table of Contents

Exploring large amounts of data with completion

Published: . Comments on Mastodon.

When faced with a large amount of information I want my computer to help me sift through it. I think I have a low “browsing-threshold” and will rather quickly turn to searching rather than paging through and reading. I already mentioned this psychological trait of mine when I complained about which-key, and the solution I proposed there was to use minibuffer completion instead of tiring your eyes. I particularly recommend this strategy to sift through data when combined with the orderless completion style —because life is too short to always remember the order words go in.

Here’s another example where I used this strategy. I’m an academic and often need to find out what journals there are in a given field and some rough idea of how selective they are. I typically use the SCImago Journal Rank database for this. I don’t agree with the use of citation metrics to evaluate academic work but (1) I need to work within a system that uses them, (2) I don’t have a good idea of what to replace them with for some use cases. If I publish a paper in a journal not listed in that database, that paper is sadly not going to help my career —and most journals are in that database, so it’s really not that hard to stick to listed journals. Also, there are times when I am asked to evaluate the work of other academics, for hiring or promotion decisions, or when writing letters of recommendation, and they’ll often have published in journals I’m unfamiliar with (since there are literally thousands of academic journals that publish math papers —and I’m sure math is small compared to many other fields!). In those case I look the journal up to get some rough idea of how hard it was to publish there. I’m the first to admit this situation is not ideal, but I don’t see how to avoid using some kind of journal ranking for some of the tasks I’m required to perform.

Anyway, I used to use the SCImago website directly to look up journals, but the user experience was lacking compared to minibuffer completion in Emacs: first, the website doesn’t show you any results at all until you press enter; second, you can only search for word fragments in journal titles. I wanted the full interactivity and search flexibility of Emacs minibuffer completion with a UI like Vertico and a completion style like Orderless —the SCImago website already supports the best Orderless feature: matching word fragments in any order; but some journals are widely known by their initials and the SCIMago website doesn’t support searching that way. And finally, I’m very, very often in Emacs when I need to look up journals, so switching to my browser to do it was a small waste of time.

Now, it turns out you can download SCImago’s data for each year in a

CSV file, so I downloaded the last several years of data. The file for

each year is around 10MB, so I filtered them to keep only journals

that publish at least some math papers, and joined the lists for each

year into a single file with around 15000 lines. The file is formatted

as a single Lisp list, one element per line, and each element

corresponds to a specific journal’s ranking in one specific topic and

year. I then wrote an Emacs command that prompts me in the minibuffer

first for a journal name, and then prompts me again, this time for a

year and finally copies to the kill-ring the lists of topics and

rankings for that journal in that year. I almost never finish that

command: after finding the journal I want to look at, I see the topics

and ranking in the second minibuffer prompt and cancel the command

with C-g.

Sometimes I’m not after a particular journal, but want a list of

specialized journals in a field. In that case I’ll run the command

type the field’s name and then use embark-export to get a buffer

listing the matching journals. In that buffer, pressing RET on a

journal title will prompt you in the minibuffer for a year in order to

copy the topics and rankings to the kill-ring. Again, I usually just

read them and press C-g. Another way I use my command is as a form of

completion: I use it to insert the full title of a journal into the

current buffer using embark-insert. All in all, having this command

has been a real time-saver.

If anyone is curious to see the code, I have it in a public repository, but I should warn people that:

- the code to download the database files for each year using

wgetno longer works, because SCImago now uses Cloudflare to check you are human (so just download them manually), and, - the code to preprocess the SCImago CSV files into a single Lisp file is written in the BQN programming language.

I really like array languages for data munging tasks, but since the point was to use the data in Emacs, I probably should have used Emacs Lisp. And I probably would have if Emacs came with a CSV parser (although BQN doesn’t come with one either…). Anyway, the point here is simply to illustrate the idea that minibuffer completion is a great way to browse information when there is a lot of it (and for me, a couple of screenfuls already counts as “a lot”).

Oh, I almost forget to mention one amusing thing about the code: in

addition to the command I mentioned above, I wrote a second command

that also prompts for a journal title but then instead of prompting

again produces a buffer in tabulated-list-mode with the topics and

rankings for each year. I never use that command because the command I

described above can emulate it: using embark-export from the second

minibuffer prompt gets you an almost identical result! You’d think

that I, of all people, would have been able to tell this other command

was subsumed by the first one and Embark…

Vim is composable

Published: . Comments on Mastodon.

I want to articulate something I find confusing. It’s not about Vim, but rather about Vim users. (And since this is an Emacs blog, I’ll also give some Emacs pointers along the way.) I used Vim for a few years and still like it a lot. When forced to edit text in a non-Emacs editor, I usually use the editor’s Vim emulation mode because there is very often a decent one.

Vim users often say that what makes Vim great is that it has a composable text editing language, and they’ll tell you that what that means is that you choose separately what text to operate on and what operation to perform on it, and can combine any operation with any way to select text. And you can choose those components in any order: in what is called normal mode you first choose an operation and then an operand; but if you prefer to do it the other way around, you can use Vim’s visual mode.

Here’s what really confuses me: Vim users never tell you that this composable editing model, of choosing separately what text to operate on and operation to perform on it, is extremely common and is built-in to almost all text editors. They also don’t say it is unique to Vim, I don’t think, but it still feels very odd to rave about composability when it is a commonplace feature. It feels like a friend excited about their new car telling you that the model he bought is crazy cool because it has tires!

Even the lowly Windows Notepad is a composable text editor: to select text you can highlight with the mouse, use shift and the arrow keys, double click to select a word, or triple click to select a line; once you’ve selected you text you can press backspace to delete it, ctrl+x to cut it to the clipboard, ctrl+v to replace it with the contents of the clipboard, etc. There’s a dearth of operations in notepad, but they all compose with the various means of selecting text.

I don’t think I’ve ever used a single text editor that isn’t

composable in the sense Vim users explain. To me that is not at all

what makes Vim special —it can’t be since all text editors do that!

What I find most special about Vim is the variety of operations and of

ways to select text. I specially like all the fine-grained

distinctions Vim has to say exactly what stretch of text you want to

act on. In Emacs I missed Vim’s distinction between words and WORDS

(the all caps one means a maximal consecutive stretch of

non-whitespace characters), so I wrote a command mark-non-whitespace

to mark the WORD at point. In Vim when you move by words you can

decide whether you want to land just beyond the end of the word or at

the beginning of the next word, which I also missed in Emacs until I

found the forward-to-word command in misc.el, which I bind to M-F.

After the sheer variety of motions, text objects and commands in Vim,

I think what I like best is the help you get in automating editing

tasks. First, commands can take a numeric repetition count. I don’t

think that is common in text editors. I’m sure there are some others

that do it but, of the ones I’ve used, only vi, Vim and Emacs do that,

that I can recall. Second, there is the marvelous dot command, that

repeats the last editing operation (I say “editing operation” as

opposed to commands that only move the cursor without modifying the

text you are editing). With n to repeat the last search and . to

repeat the last editing command, you can really fly over text making

parallel edits all over the place: n.n.nn. (two n’s in a row because I

wanted to skip one search result!). And third, there are keyboard

macros to automate more complex tasks. I haven’t used VS Code, but I

have heard it doesn’t have keyboard macros (except maybe in a plugin),

which sounds like a very hostile-to-automation way to design a text

editor.

Of course, Emacs also has ways of repeating the last command; there

are repeat and repeat-complex-command, for example. But the experience

in Vim with . is smoother and it illustrates a subtlety about the

composable editing model: Vim’s . repeats the last combination of an

editing operation and text selection, those two parts are fused

together into a single repeatable unit. I guess you could say that is

a sense in which Vim is composable and many other editors are not

(though I don’t often see Vim users making this point; they tend to

explain what they mean by composability as I did above, accidentally

describing every text editor in existence). In Emacs when you use

repeat or repeat-complex-command you only get the last Emacs command

repeated, which might only be half of the fused operation-selection

whole. To get an experience more similar to Vim’s . in Emacs, you can

try the dot-mode package, which makes a keyboard macros out of the

last consecutive stretch of buffer-modifying commands. In a way, I

like it even better than Vim’s . command, because, and this will sound

funny: it’s a little less stressful to use for certain personality

types. In Vim I constantly paused to think: “can I do the next edit in

a single command so that I can repeat the whole thing with .?”, and

would be disappointed in myself whenever I made an edit using two or

more commands, soon after needed to repeat it and hadn’t though to

record a macro, and doubly disappointed if I then realized I could

have done it in a single command! With dot-mode you can relax: you get

all the consecutive editing commands you made repeated, not just the

last one.

Nowadays I don’t even use dot-mode in Emacs anymore, sticking to

keyboard macros. But I have made their use as frictionless for me as

possible. First, I bind kmacro-start-macro-or-insert-counter to M-r

and kmacro-end-or-call-macro to M-m, where find I them more readily

accessible than at the default bindings of <f3> and <f4> (specially

since on my laptop I need to press the fn key to use functions keys).

And I bind M-n to a command that repeats the last isearch so I can

play the n.n.nn. game in Emacs too by holding down the meta key and

going nmnmnnm:

(defun isearch-next ()

"Go to next isearch match."

(interactive)

(if (equal isearch-string "")

(user-error "No previous search.")

(let (isearch-lazy-highlight)

(isearch-repeat 'forward))

(isearch-exit)))

Now let me get back to what I like about Vim: so far I’ve said (1) variety of operations and way to select text, especially the fine-grained selection distinctions, (2) features for automation: repeat counts, the dot command and keyboard macros. To that I’d add (3) the concept of buffer: that text need not reside in a file to be edited in Vim (this is also a key idea in Emacs, of course), and I very often put text in a new temporary buffer to save it for later or to edit it quickly and paste somewhere else; and, of course, (4) extensive customizability. As you can see what I like about Vim is basically also what I like about Emacs. What can I say? When it comes to text editors I definitely have a type!

Of course, some Vim users do also mention all the other neat features of Vim that I like, but why are there so many blog and forum posts about Vim’s composability that don’t mention this is the normal way for text editors to be designed? Here are a few conjectures, none of which I really believe:

- Vim users who talk about composability have never used any other text editor and don’t know those are composable too. This would explain the situation but seems exceedingly unlikely.

- Vim users think that Vim does composability better than other

editors but fail to explain in what ways is better and wind up

describing composability in a way that other editors also have. This

is possible: explaining things is hard (I do it for a living and am

still terrible at it); and there are ways in which composability in

Vim is better, namely the

.command repeating an edit comprising an operation-selection pair. - Vim users don’t really believe other text editors lack

composability, what truly bothers them is that in addition to

composability other editor also offer as shortcuts some fused

operation-selection combos. For example Emacs will let you mark a

region by any means you wish and then compose that with a

kill-regioncommand, but it also offerskill-word,kill-line,kill-sentence,kill-paragraph, etc. Maybe what Vim users really like is Vim’s principled insistence in not offering shortcuts, making you always specify an operation and a target text separately? I don’t think this either matches what they say or makes much sense really —why would it bother you that other software offers additional shortcuts?. (Also, Vim does have a few shortcuts: for example, in insert mode<C-w>deletes the previous word.)

To me the prevalence of people saying “Vim is great because it is composable” and then explaining composability in a way that applies to every text editor I’ve ever used is just one of life’s mysteries.

Elevator pitch

Published: . Comments on Mastodon.

Software is generally terrible. It’s buggy and slow, despite computers being ridiculously fast. And even when it’s not buggy it often does something weird or that isn’t quite what you want. When I saw the call for this month’s Emacs Carnival asking for elevator pitches for Emacs, I started collecting bugs and oddities in the software I use. I don’t want to pick on some poor indie programmer, so here’s a list of bugs or odd behaviors I’ve observed during just this month in software from Google and Facebook:

- A boat load of YouTube bugs or quirks:

- Play/pause button doesn’t always show the right state.

- The speed control UI is randomly selected among about 3 different ones.

- Sometimes when double tapping to rewind 10 seconds, the playback speed is reset to 1x.

- Changing the playback speed sometimes does nothing.

- Sometimes when you open the Android app, you get a tiny black rectangle in the corner that I can’t figure out how to interact with. I wind up just restarting the application.

- In the YouTube Music app, finished podcast episodes sometimes don’t show up as “played”. Leaving the list of downloaded episodes and returning to it fixes this.

- On the Facebook webpage the animations for reactions don’t load for me anymore. (Luckily hovering on the blank space shows a tool-tip stating which reaction it is.) I’d be perfectly happy with static images or even text…

- The Google search page can be configured to match your system dark mode preference. But it isn’t fully automatic, for a change to register, even in brand new browser tabs, you have to reload (or go into settings, not to change anything, just going into settings is enough!).

- The battery indicator on my Android phone occasionally doesn’t show that the phone is plugged in until I reboot it.

And there’s nothing I can do about any of this! I guess I could try to report the bugs and hope someone fixes them, but the play/pause problem seems to be about a decade old from what I’ve read online so I’m not holding my breath.

My elevator pitch for Emacs is simply: you don’t have to put up with any of this crap in Emacs! You can just fix any bug or behavior you dislike without waiting for anyone! I often notice something I don’t like, fix it in my personal configuration, and only afterwards report the bug (and usually I then monitor updates to that piece of software to see when I can remove my personal workaround).

Now, you might think the problem is that I use proprietary software, and that if I only used open source software all my computing experience would be Emacsian, that I’d be fixing bugs left and right. No, I wouldn’t! Emacs makes this as frictionless as possible. For most open source software I use, I don’t even have the source code installed (because that’s not the default in Debian’s package manager: I’d have to go out of my way to get the source code). Even if I had the source code, it would be hard to figure out where the code responsible for the behavior I want to change even is and I’d have to restart the program to test any changes I make, probably several times. With Emacs this is all a breeze, I can:

- jump directly to the source code of the command that I just used (and if I don’t know what command that is, or what keys I pressed to cause it to run, I can ask that too);

- make any modifications and try the new code immediately without restarting Emacs;

- when I get it right, I can add code to my personal configuration incorporating the fix without touching the original source code.

I know myself: I need all of that convenience to fix problems or I just won’t do it. Most fixes take a few minutes and that’s the only reason I’m willing to make them. I’ve gotten pretty good at making Emacs do exactly what I want and I’m not a software developer, I imagine that for them the experience is even smoother!

Ten things to try with Embark

Published: . Comments on Mastodon.

This is my first listicle! (I apologize in advance for it, and hope not to do this too often.) Here are 10 not-so-obvious things to try with Embark, written as a response to this reddit question.

I’ll use <act> to represent whatever key binding you have

for embark-act, and <dwim> to denote the binding for embark-dwim.

- If I’m looking at some project’s README file and it mentions some

command I should run (for example, to install the project), I don’t

copy the command, start or switch to a shell, and then paste the

command. Instead I select the command, and use

<act> M-!(or<act> M-&) to directly pass the command toshell-command(orasync-shell-command). Notice thatM-!is just the global binding forshell-command. In embark you can use any command as an action, you are not limited to the commands in the embark keymaps (those keymaps are just for convenience); you can specify the command with any key binding you have for it, or even by usingM-x. (I’ve been asked more than once to remove this freedom and limit users to pre-registered commands from the embark keymaps, which seems insane to me, and I refused all such requests!) - I use jinx for spellchecking in both English and Spanish, and

sometimes I want to add a word (usually a proper name) to my

personal dictionaries for both languages. To do that I take

advantage of the fact that while

jinx-correctis running, that is the default action, i.e.,embark-dwimwill runjinx-correct. So if I haveembark-quit-after-actionset tonil(which I prefer), I can add the word to one dictionary using<dwim>instead ofRET, and this keepsjinx-correctopen so I can still add it to the other dictionary (this time usingRET, sojinx-correctnow finishes). - Similarly to the previous example, when writing an email I can run

mml-attach-fileand useembark-dwimto attach several files in one go. This is useful because I often need to attach several files from the same directory, and using a single run ofmml-attach-filesaves me from having to navigate several times to the directory. In fact, often the files I need to attach all have something in common in their name, say, I need to send all files of the formreport-$MONTH-2025.pdf. Then I can runmml-attach-file, navigate to the directory containing them, typereport 2025, which under Orderless will match exactly the files I want, and then run<act> A RET, which will run the default action (attaching) on all of them. - If I’m reading Emacs’s info documentation, and it mentions some

command I want to try, I put point on the command name and use

<act> x(for commands,xis bound toexecute-extended-command). If it mentions some variable and I want to customize it,<act> u(for variables,uis bound tocustomize-variable). I used to copy and paste a lot more, to get inputs to commands, but Embark let’s me send things directly to the commands that use them. - Any command that prompts for widgets becomes a widget manager! For

example, I use dired a lot less than I used to, since I now do most

of my file management from inside

find-file: I useembark-actfrom insidefind-fileto delete, rename, copy, or open files with external programs. Similarly, I do most package management from insidedescribe-package, usingembark-actto install, uninstall, view the homepage or description for a package. Similarly, if I want to toggle, customize, or find out the current value of a variable, I’ll do it fromdescribe-variable. I usefind-librarynot just to open a library, but also to load one, or to view the commentary or info manual. I only need to remember (or even have) the key bindings for the commands I use as entry points, and Embark reminds me of the rest. - If see you some arithmetic operations written in a buffer

somewhere, you can print the result in the echo area by selecting

that text and sending it to

quick-calcwith<act> C-x * q(if you do this often, you might want a better keybinding forquick-calcthan the defaultC-x * q). With a universal prefix argument,quick-calcwill insert the result in the buffer instead of just echoing it; I used this to compute that 30! = 265252859812191058636308480000000. Similarly if you want to add a column of numbers, select the numbers and use<act> :(for regions,:is bound tocalc-grab-sum-down). - I even use

<dwim>instead ofC-x C-eto evaluate expressions for several reasons: (1) my keybinding forembark-dwimis shorter thanC-x C-e, (2) I can place point either before the opening parenthesis or after the closing one (or even use<act>from anywhere in the middle of the s-expression and cycle to the s-expression target), (3) the default action in Embark for s-expressions ispp-eval-expression, so you get pretty-printing too! Another nice action on s-expressions isembark-eval-replace(bound to<), which replaces the s-expression with its value. - Sometimes I’ll use

M-!to run a shell command and while I’m typing the full command realize I forgot exactly how you use the program (maybe I forgot what an option is called, or the order of the arguments), in that case, I put point on the command name and run<act> M-x manto pop up the man page while I keep working on typing in the command. - Embark tries to use the same key binding for conceptually similar

actions. For example

hisdescribe-symbol,describe-face,finder-commentary, ordescribe-packagedepending on what you act on. I try to extend that as much as possible in my personal configuration. For identifiers in programming modes that are not Emacs Lisp, Embark bindshtodisplay-local-help, which isn’t very useful on its own, but you can remap it to something better, For example, in shell script buffers (and in shell buffers) I remapdisplay-local-helptoman, and in perl-mode buffers I remap it tocperl-perldoc. That way I can still get help for the thing at point with<act> hin those buffers. - I use

org-ql-findorconsult-org-headingto search my org files and I useembark-actto do things to the headings right from the minibuffer without losing my place. Particularly useful areIandOwhich are bound toorg-clock-inandorg-clock-out. To link to a heading, I used to navigate to the heading, useorg-store-link, navigate back to where I wanted the link (usually easy by popping the global mark) and then useorg-insert-link. But now, I just search for the heading I want to link to with org-ql or consult, and use<act> jto insert the link, it’s super fast and convenient, and I find myself interlinking my notes much more now (I guess this is one of the things people like about org-roam, too). Similarly if I want to link to a bunch of headings I can usually craft and org-ql query that matches exactly the ones I want, then I use<act> A l, to callembark-act-allwithorg-store-linkas the action, and finally I useorg-insert-all-linksto insert all links as an itemized list.

Writing Experience

Published: . Comments on Mastodon.

This blog entry is part of the Emacs Carnival for July 2025, hosted by Greg Newman, with the topic of “Writing Experience”.

I mostly use Emacs to write prose, not because I don’t also use Emacs to write computer programs, but simply because I write a whole lot more prose than code! I write papers, lecture notes, homework assignments, notes on different topics (some public, some private), my website including this blog, emails, comments on social networks, and I’m even supposed to be keeping a journal (though I notice the most recent entry is from April…).

But more than that, I tend to write any bit of text longer than a

sentence or two in Emacs. The main the reason for that is that I edit

a lot as I write and Emacs makes this easier than any other text

editor I’m aware of. Before Emacs I used Vim and, while it is a very

powerful text editor, it has distinct modes for inserting text (called

insert mode, naturally) and for editing it (called normal mode, to

mock writers for being imperfect and normally requiring editing). The

separation of modes nudges you in the direction of getting a first

rough draft down and then editing it. That suits some people

perfectly, and it is certainly something I could do and was used to,

but I think that I am naturally more of an edit-as-you-go person. My

evidence for this is that it is what I do in Emacs, which favors

neither the draft-first nor the edit-as-you-go style ―it’s pretty much

the same number of keystrokes either way, unlike in Vim where you give

the poor ESC key a break if you batch your edits.

By the way, the fact that I spend so much time editing prose is also

why I need a text editor like Emacs or Vim and couldn’t switch to a

code editor like VS Code. When an editor calls itself a “code editor”,

my impression is that it does so to signal poor support for prose (or

maybe it wants to signal good support for code ―I needn’t be so

negative). I don’t think VS Code has commands to move by or select

sentences, for example; instead it’s line-oriented, which makes sense

for programming ―or, I guess, for people who write prose one sentence

per line because they use git and want cleaner diffs but don’t know

about git diff --word-diff.

Emacs is very powerful out of the box for editing prose, but even so I have a few personal tweaks to make it fit me like a glove. In the rest of this blog post I will describe a few commands I use when editing prose, some built-in, some I wrote myself to scratch a small but persistent itch.

Changing case and transposing

One of my most common typos is being slow to release the shift key and

accidentally capitalizing the first two letters of a word, as in “See

you next THursday!”. When I make that mistake I often notice it before

I finish typing that word and in stock Emacs I could fix it right away

with M-- M-c or M-b M-c. (By default M-c is bound to capitalize-word,

but I recommend rebinding it to capitalize-dwim which acts as

capitalize-word unless there is an active region in which case it acts

as capitalize-region.) At some point I noticed that my most common use

of M-c was to capitalize the previous word, and decided to simplify

that case. Initially I wrote a command that is just like

capitalize-dwim except that if point is at the end of the word it acts

on the previous word rather than on the next one. That did simplify my

most common usage of M-c but it introduced a new problem: when I

wasn’t fixing a typo in a word I just entered, I often forgot the new

behavior and expected M-c to capitalize the next word, even if point

was at the end of a word; in those cases my new command annoyed me

quite a bit.

This illustrates what I feel is an underappreciated point: the user

experience (UX) of even simple editing commands is often tricky to get

exactly right. Of course, people are aware that UX design is hard, but

I think people tend to assume it’s only hard for larger programs, not

for something tiny like capitalize-word. But for a command you are

likely to use many times a day getting the UX exactly right really

pays off. I eventually fixed my command drawing inspiration from a

different set of commands that are also extremely useful while writing

prose: the tranpose family of commands. I’ll explain the feature of

these commands that I adopted for the case change commands, after I

explain what they do. The transpose commands are fantastic and I don’t

understand why not every editor has them (even Vim doesn’t!). Another

extremely common typo I make is swapping two charcaters. To fix that,

you put point on the second of the characters (if your cursor is a

bar, put the bar between the swapped characters) and use

transpose-chars, bound by default to C-t. There are also

tranpose-words (M-t), transpose-sexps (C-M-t), transpose-lines

(C-x C-t), transpose-sentences and transpose-paragraphs.

The sexp and line commands are more useful for editing code than

prose, but are still useful for prose, particular since parenthetical

expressions or quoted text count as sexps. It’s a little sad that the

sentence and paragraph commands are not bound by default; I bind them

to M-T and C-x M-t respectively. While transpose-chars is most useful

for fixing typos, the other transpose commands are more useful while

editing. I find I rearrange text quite a bit: Even for a 5−10 line

email I’m fairly likely to have swapped two sentences or even two

paragraphs while writing it!

The transpose family of commands have a few very nifty features:

- They leave point after the second of the two swapped things, which means that by simply repeating the command you can continue to move that thing to the right. With a negative prefix argument you can drag things to the left instead.

- With a prefix argument of 0 they can swap non-adjacent things! Select a region starting somewhere in the first thing and ending somewhere in the second and call a transpose command with a prefix argument of 0 to swap them,

- If you use

transpose-charsat the end of a line you might think it would swap the last character of the line with the newline, since, that newline is after all the next character, but instead it swaps the last two characters on the line. This means that if you accidentally swap two characters while entering text (at the end of some line) and notice the typo immediately, you can fix it with justC-twithout moving the point! This is special behavior oftranspose-chars, sadly not shared bytranspose-words, but at least that one has a similar but lesser magic: if you usetranspose-wordsat the end of the buffer (yes, I said “buffer”, not “line”), it will… not swap the last two words, but produce an error message. and also move point to before the last word. But that very last bit means that a secondM-twill swap the last two words! OK, kind of lame compared toC-tbut at least it’s something.

That last behavior of transpose-chars is what I adopted for my

versions of the case-change dwim commands: if you call one of my

case-change commands at the end of a line, it changes the case of the

last word of the line (not the first word on the next non-blank line,

which is what capitalize-word or capitalize-dwim would do). And that

feels perfect to me: my common typo is fixed with a simply M-c but

while editing text in the middle of the text I don’t get any

unpleasant surprises anymore. Try teaching that to a web browser text

input box!

Marking whole words

Another tiny annoyance I had with the built-in commands is that the

marking commands only mark from point to the end of the thing they are

for. For example mark-word does not mark the word at point, it marks

the portion of that word starting at point (so if point is on the

first character of the word, it does mark the entire word). The

analogous command for sentences has more honest name:

mark-end-of-sentence ―though mark-to-end-of-sentence would be even

clearer. Now, for sentences, that behavior seems fine and useful to

me, since I often do want to grab just the tail of a sentence, but I

basically never want to mark just a piece of a word. So I wrote a

command that marks the entire word point is on, bound it to M-@ and

just use it in place of mark-word. Obviously I called my command

mark-my-word.

Useful commands with no default key binding

That mark-end-of-sentence command I mentioned doesn’t have a default

key binding, but that’s OK since you can achieve the same effect by

using shift selection with the forward-sentence command (I mean typing

M-E). But there are some very useful commands, particularly in the

misc.el library, with no key binding:

zap-up-to-char, which I find I want more often thanzap-to-char, so I bind this oneM-zandzap-to-chartoM-Z.forward-to-wordandbackward-to-wordwhich move to the opposite end of the word thanforward-wordandbackward-worddo; I bind these toM-FandM-B.copy-from-above-commandandduplicate-dwim, two commands that can duplicate a line. The first duplicates the line above point and the second duplicates the line at point. The first command actually duplicates the tail of the line above starting from the current column, and if given a numeric argument will only duplicate that many characters (I hardly ever use this last bit of functionality since I find counting characters tedious and error prone). The second command will duplicate the region if it is active ―which is whatdwimmeans in several Emacs commands.delete-forward-charis a surprising one: by defaultC-dis bound todelete-charbut the documentation for that command says: “The command ‘delete-forward-char’ is preferable for interactive use, e.g. because it respects values of ‘delete-active-region’ and ‘overwrite-mode’.” I agreed and reboundC-d.kill-paragraph, I bind this toM-K.up-listmoves you out of a delimited expression, which honestly is more useful when writing code, but I mention it here since I do use it often for getting out of parenthetical remarks or quotation marks. I bind toC-M-owhich goes well with the other sexp navigation commands withC-M-modifiers; the mnemonic forois that it gets me Out of a sexp.transpose-sentencesandtranspose-paragraphsI already mentioned above. I bind them toM-TandC-x M-t. In org-mode buffers you don’t really needtranspose-paragraphssinceM-<down>andM-<up>cover its functionality.

Dabbrev

The kind of “autocompletion” I almost always want while writing prose

is simply to complete text I’ve already typed somewhere. For that

dabbrev-expand (bound to M-/) is super useful: it’ll search for

completions of the beginning of a word you’ve typed in several places

in order: the current buffer before point, the current buffer after

point, other buffers in the same major mode as the current buffer, and

finally all other buffers. (That’s just the default configuration, as

usual in Emacs, dabbrev is quite configurable.) I often find myself

opening some file just so I can complete words from it in another

buffer. One lesser known feature of dabbrev-expand is that you can

also use it to complete phrases, not just words: if right after

completing a word using dabbrev-expand you insert a space and then run

dabbrev-expand again, it will insert the word that followed the first

word wherever it found it. So M-/ SPC M-/ SPC M-/ ... will complete a

phrase from your buffer. To make this even more convenient I wrote

this little command that I bind to M-;:

(defun dabbrev-next (arg)

"Insert the next ARG words from where previous expansion was found."

(interactive "p")

(dotimes (_ arg)

(insert " ")

(dabbrev-expand 1))

(setq this-command 'dabbrev-expand))

That way I can complete a phrase with M-/ M-; M-; .... You can really

fly that way. For example, the previous paragraph says “current

buffer” three times; I only wrote the first one in full, the others

were cur M-/ M-;.

Ediff

This one isn’t so impressive to computer programmers, used as they are

to source control, but let me tell you that the ease with which you

can merge versions of files using ediff will absolutely blow

mathematicians minds! I’ve impressed several coauthors by merging our

changes to a draft paper in less than a minute, flying over changes

faster than they can orient themselves. It feels like a super power to

people who haven’t seen something like it before.

Keyboard macros

I don’t think it would surprise anyone to say that keyboard macros are very useful for automating edits while coding, but perhaps it is a little surprising they can also be very useful while editing prose. One thing that comes up fairly often for me is that I want to write a bulleted list and I have the raw data I need to talk about in some other format. For example I might have a spreadsheet (if it’s shared) or an org table (if I’m the only one editing) with a list of names, email addresses and affiliations of some people and I need to write a small paragraph about each person. Here’s an example with fake people:

| Juana Sinisterra | jsinis@uni.junco | Universidad del Junco |

| Molly Edwards | medwards@henkin.edu | Henkin College |

| Mario Finetti | mfino@vallebruna.it | Universitá di Vallebruna |

And I want to turn it into:

- Juana Sinisterra <jsinis@uni.junco> from Universidad del Junco, XXX.

- Molly Edwards <medwards@henkin.edu> from Henkin College, XXX.

- Mario Finetti <mfino@vallebruna.it> from Universitá di Vallebruna, XXX.

where the “XXX” are placeholders I’ll fill in later. (I’d actually use

<++> as the placeholders and fill them in using my placeholder

package, but never mind that now.) For this I’d record a keyboard

macro that transforms a single row of the table and just run it for

each line. For dealing with keyboard macros I prefer the “modern”

interface, consisting of kmacro-start-macro-or-insert-counter (bound

to <f3>) and kmacro-end-or-call-macro (bound to <f4>), which can be

used in place of all four of these “old” key bindings: C-x (, C-x C-k

C-i, C-x ) and C-x e. However I find the function keys a little too

far for comfort, so I rebind the commands to M-r (for “record”) and

M-m (for “macro”). (M-m is bound by default to back-to-indentation, a

command which I do use but rebound to the more mnemonic M-i; M-r also

has a default binding, but I never use that command). Since I switched

to the simpler “modern” macro commands I find that I use keyboard

macros a lot more, and rebinding them to the highly accesible M-r and

M-m keys gave my macro usage a further boost.

In the example I gave above, I wanted to run the keyboard macro to

every line of a table. You can do that by recording the macro, marking

the remaining lines and using apply-macro-to-region-lines bound to C-x

C-k r. That key binding is a little awkward and to be honest I don’t

use it: Embark binds that command to m when you are acting on a

region, so I use C-. m (simpler key bindings are a nice perk of

Embark’s contextuality). But there is further convenience to be

enjoyed: as in this example, I very often want to apply a macro to

every line of a “paragraph” (a table with a blank line after it

counts), or rather, to the remaining lines of a paragraph after

recording the macro for the first line. For that I wrote this simple

command I bind to M-M:

(defun apply-macro-to-rest-of-paragraph () "Apply last keyboard macro to each line in the rest of the current paragraph." (interactive) (when defining-kbd-macro (kmacro-end-macro nil)) (apply-macro-to-region-lines (line-beginning-position 2) (save-excursion (end-of-paragraph-text) (point))))

It feels like magic: M-r, do stuff to the first line, M-M and boom,

the same transformation gets applied to the rest of the lines!

The case against which-key: a polemic

Published: . Comments on Mastodon.

It’s Friday and jcs over at Irreal has started a tradition of being

polemical on what he calls Red Meat Fridays. I’m joining in on the fun

today to explain why I don’t like which-key ―but going somewhat

against the red meat spirit I don’t want to merely criticize: I’ll

offer up a suggestion of something better at the end, too.

What which-key-mode does is popup in the echo area a list of key

bindings and commands found under the current prefix. Here’s what it

looks like after I pressed C-x C-k waited a second for the popup to

appear:

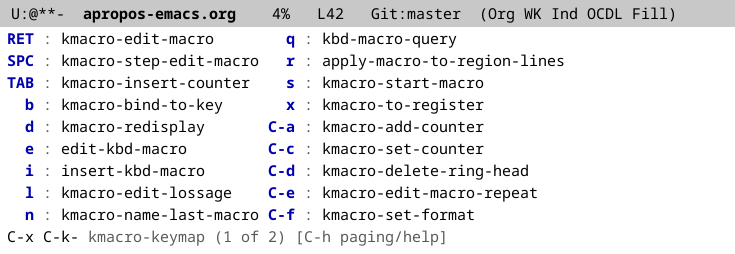

Since the commands under C-x C-k didn’t all fit on a single page,

which-key splits them into multiple pages and you can advance through

them with C-h n and C-h p. Reading through the which-key popup is a

great way to learn what is bound under a prefix. People love this and

which-key is now bundled with Emacs.

So why don’t I like it? There’s a minor reason and a major reason. The

minor reason is simply that it is automatic by default. The default

configuration has the which-key popup appear 1 second after typing a

prefix. Some people love this because it pops up precisely when they

don’t know or can’t remember what key to press next. I dislike almost

all forms of automatically appearing UI finding them jittery and

distracting; I almost always prefer to summon UI explicitly with a key

press or maybe mouse action. I understand this only a personal

preference, and it is an easily fixed one at that! There is a simple

way to configure which-key to wait for you to type C-h to appear:

(setq which-key-show-early-on-C-h t

which-key-idle-delay 1e6 ; 11 days

which-key-idle-secondary-delay 0.05)

So that was just a small matter of personal preference, what’s the

major reason at the heart of this polemic then? It is this: I believe

we should use computers for automation, to assist us in finding

information. Clearly which-key-mode has a different philosophy: it

merely displays all the key bindings under a prefix and then lets

humans do all the work! A human has to read the key bindings, possibly

paging through a couple of pages them. It feels ridiculously to be

sitting at a computer, a very powerful information retrieval machine,

equipped with a high bandwidth input device (namely: a keyboard) and

to read a bunch of boring text as if it were printed on a piece of

paper (or two or sometimes even three pieces of paper!)

Now, sometimes you do want to read all the key bindings under a

prefix, to find out or to refresh your memory about what’s there. In

those cases I have no problem with which-key’s approach, but I find

that most often I’m looking for a specific key binding and I remember

a portion of the command name or maybe a bit of the binding (some

Emacs key bindings are long enough that I can remember them

partially but not completely!) When I’m looking for a specific

binding, I really want the computer to do the searching for me, that’s

what the damn thing is for!

And now I’ll tell you about the improved which-key I promised at the

start. It has all the paper-like functionality of which-key, but

additionally will help you search instead of patiently waiting while

you to do all the work yourself. This replacement is a function called

embark-prefix-help-command that comes with my Embark package. To use

it simply (setq prefix-help-command #'embark-prefix-help-command). The

prefix-help-command variable controls what happens when you press C-h

after typing a prefix. What embark-prefix-help-command does is prompt

you in the minibuffer, with completion, for a key-binding−command pair

under the current prefix. You can view your options or type some input

in the minibuffer to narrow the listing. It is best paired with a

minibuffer completion UI that automatically displays the current

completion candidates in real time as you type. (I discussed several

of these in another blog post: My quest for completion.) I recommend

Vertico, because it has an option to display completions in a grid,

which makes embark-prefix-help-command look a lot like which-key:

(vertico-multiform-mode) (add-to-list 'vertico-multiform-categories '(embark-keybinding grid))

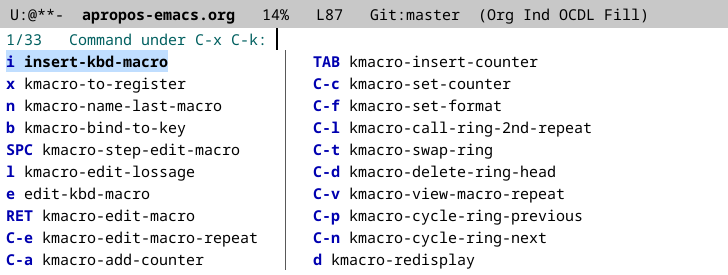

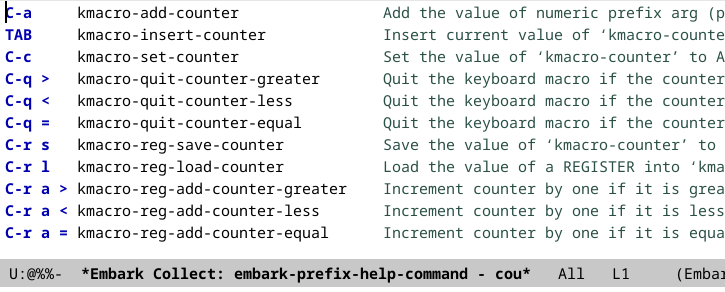

Here’s what that looks like, for the same C-x C-k prefix as above:

You could use this just like which-key, reading all the commands and

key bindings; Vertico even lets you use C-v and M-v to page through

the results (which I find slightly more comfortable than the default

in which-key of C-h n and C-h p). But you can also use the minibuffer

input to narrow the options. This works best if you have a completion

style that lets you type a substring from anywhere inside a candidate

to match it. I recommend the Orderless completion style, or I wouldn’t

have written it, but the built-in substring completion style works

too. Say I was trying to remember a key binding for some command that

deals with keyboard macro counters ―see (info "(emacs) Keyboard Macro

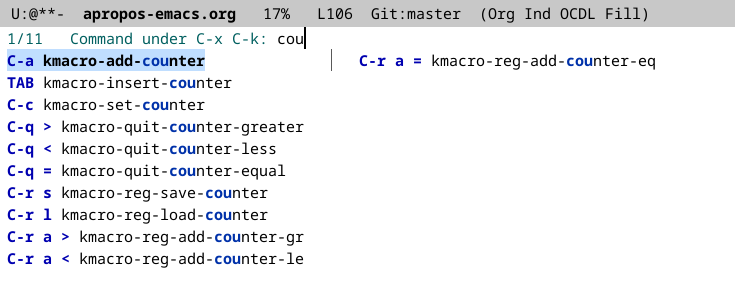

Counter") if you haven’t heard of these. Then you just type “cou” and

get this:

You can also narrow by a part of the key binding rather than the

command name. For example, I’m writing this blog post in org-mode and

have inline images displayed, but when you add a new one that one is

not displayed automatically. I could toggle the display of inline

images off and on again with C-c C-x C-v, but I remembered there was a

key binding for that, under the same C-c C-x prefix that involved v

with some other modifiers, so I typed C-c C-x C-h and then “-v” and

saw that C-M-v was the rest of the binding I was looking for.

This UI is very flexible: besides the narrowing via completion, you

can do lots of other things. You can can navigate with C-n, C-p or the

arrow keys among the completion candidates, press RET on a command to

run it, and you have the full power of Embark: say you have embark-act

bound to C-., then you can press C-. h when a candidate is displayed

to show its documentation, or C-. d to go to its definition, or C-. w

to copy the command name to the kill-ring. Or say you want to explore

some subset of the commands more in depth, you can narrow to the

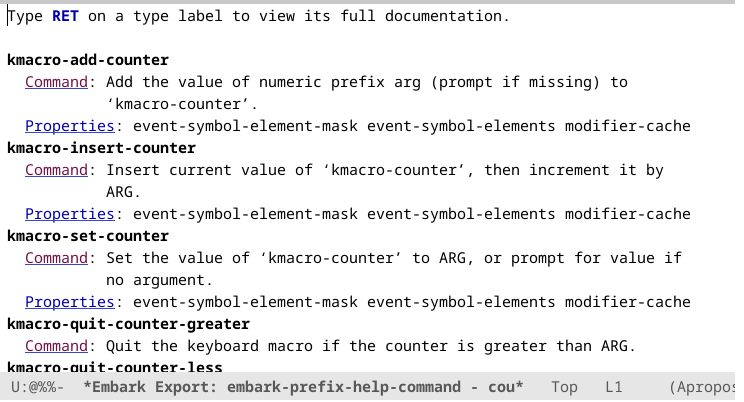

subset you want and run embark-export (with C-. E) to get a nice

apropos-mode buffer with a summary of those functions, like this one:

Or say, you wanted a little table of those keyboard macro counter

commands and their key bindings. Instead of embark-export you’d use

embark-collect to get this buffer:

From there I copied the first two columns as a rectangle, plopped them

into this org-mode buffer, added a few pipe symbols (using

string-rectangle), and a header, to get this table:

| Key | Command |

|---|---|

| C-a | kmacro-add-counter |

| TAB | kmacro-insert-counter |

| C-c | kmacro-set-counter |

| C-q > | kmacro-quit-counter-greater |

| C-q < | kmacro-quit-counter-less |

| C-q = | kmacro-quit-counter-equal |

| C-r s | kmacro-reg-save-counter |

| C-r l | kmacro-reg-load-counter |

| C-r a > | kmacro-reg-add-counter-greater |

| C-r a < | kmacro-reg-add-counter-less |

| C-r a = | kmacro-reg-add-counter-equal |

I hope this taste of the flexibility of embark-prefix-help-command

whets your appetite for more.

Emacs keymaps can have helpful and even dynamic prompts

Published: . Comments on Mastodon.

Nowadays M-o is unbound in Emacs by default, but it used to be used

for changing fonts in enriched text mode buffers. Enriched text is

what I consider an obscure format that Emacs supports pretty well for

some reason. I think rms had hopes of basing some Emacs word

processing functionality on enriched text, but I’m a little hazy on

the history ―which I’d love more knowledgeable people to educate me

on. Enriched text (not to be confused with Microsoft’s Rich Text

Format) is the MIME text/enriched type defined by internet RFC 1563.

In Emacs its supported by the built-in enriched library ―see

(finder-commentary "enriched").

Now that M-o is unbound by default, I recommend binding it to

other-window and turning off repeat-mode for that command with (put

'other-window 'repeat-map nil) so you can switch to another window and

type a word starting with “o” without trouble ―therwise you wind up

with an o-less word in the next window! In fact, I already used that

binding back when M-o was used for enriched text fonts.

But enough rambling, the reason I’m talking about this is that back

when M-o was bound to facemenu-keymap, pressing it would show this

message in the echo area:

Set face: default, bold, italic, l = bold-italic, underline, Other…

That’s right: M-o was bound not to a command, but to a keymap, and

pressing it would show a message in the echo area!

One day redditor sebhoagie, asked how to display a dynamic message

when a keymap is active, and I had that curiosity about M-o filed away

in my brain. I didn’t know what exactly M-o was bound to at that point

in time, but I did now it was a keymap, because I had attempted to use

C-h c M-o only to have describe-key-briefly wait for more input. So I

set out to find out how that keymap did its magic. I ran emacs -q,

found out what M-o was bound to by default (recall that I was using it

for other-window), and here’s the result (this is mostly what I wrote

on reddit back then, with the code modernized a bit):

You can add a prompt for the prefix keymap when you create it, and also prompts for the individual keys bound in the keymap! For example, the following code defines a keymap for package-related operations:

(defvar-keymap pkg-ops-map

:name "Packages"

"h" '("describe" . describe-package)

"r" '("reinstall" . package-reinstall)

"a" '("autoremove" . package-autoremove)

"d" '("delete" . package-delete)

"i" '("install" . package-install)

"l" '("list" . list-packages))

(keymap-global-set "C-c p" pkg-ops-map)

(Here I’m using the recent family of commands, macros and functions

for dealing with keymaps, keymap-set and friends from keymap-el, which

only accept the key description strings that kbd uses; I recommend

these above the older define-key and friends.)

Now, as soon as you press C-c p the following message appears in the

echo area:

Packages: list, install, delete, autoremove, reinstall, h = describe

Notice that Emacs cleverly noticed that for the key h you gave the

prompt “describe”, which does not start with h, so it actually prints

h = describe. The other prompts do start with the letter they are

bound to, so Emacs just lists the prompt you gave.

Of course, if you don’t give a prompt for a binding, it’s not

mentioned in the overall prompt for the keymap, but the key is still

bound. For example, if you replace '("reinstall" . package-reinstall)

with a simple 'package-reinstall in the above code, then the prompt

will change to:

Packages: list, install, delete, autoremove, h = describe

but r will still be bound to reinstall-package.

Now, sebhoagie said that they had an application in mind for which they wanted the prompt to change dynamically, so this trick wasn’t good enough. And I remember thinking: “Emacs Lisp is super imperative, I bet keymaps are mutable!”. I was right and as a proof of concept I cooked up this little example:

(defvar count 0)

(defvar-keymap counter-map

:name "Dynamic counter!"

"i" '("increment" . inc-counter)

"r" '("reset" . reset-counter))

(defun update-counter-map-prompt ()

(rplaca (last counter-map) (format "Counter is at %d!" count)))

(defun inc-counter ()

(interactive)

(setq count (1+ count))

(update-counter-map-prompt))

(defun reset-counter ()

(interactive)

(setq count 0)

(update-counter-map-prompt))

(keymap-global-set "<f5>" counter-map)

After running that code, try <f5> i a few times to watch the counter

increment or <f5> r to reset it back to zero.

If you are a keymap description you might think you are set for life and

just kick back and relax, but you are as rplaca-ble as anyone else.

My quest for completion

Published: . Comments on Mastodon.

This is the entry I would have written for the “Take Two”-themed Emacs carnival if it had taken me less than a month to decide to participate. It’s about all the myriad minibuffer completion UIs I’ve been through as an Emacs user, and is quite long because I’ve tried so many!

Just to make sure we’re on the same page: Emacs commands prompt for

user input in the minibuffer and offer completion, which means some

sort of assistance typing sensible inputs. There are many possible

user interfaces for this in Emacs and I’ve tried many but all of them

(By the way, this is a constant in my Emacs usage: I try many but not

all of the options, since there are always too many. For example, of

the built-in ways to list buffers I’ve used switch-to-buffer, ibuffer,

electric-buffer-list and several third party options ―I currently

use consult-buffer from the Consult package― but I’ve never tried

the built-in bs-show, for example. Similarly, of the built-ins I’ve

only used GNUS to read email and RSS feeds, but never tried Rmail for

email or NewsTicker for RSS; let alone trying all third party options

―I did use mu4e for email for a bit and elfeed for RSS feeds!)

Just so this doesn’t take forever to write, I will write it all from memory, and let people correct me on details I get wrong ―it’s only fair since I do that to other people all the freaking time (it’s a wonder I have any friends). This list attempts to be in chronological order of my usage, but I’m sure I’m getting some of this slightly wrong (and fortunately no-one is likely to be able to call me out about errors in the ordering of my personal usage of these UIs).

Default completion

In my early days as an Emacs user I simply used the default completion

UI. This UI doesn’t not show the completion candidates all the time.

If all the candidates have the next bit of text in common, pressing

TAB inserts it into the minibuffer (people call this TAB completion).

I’ve always found this funny since it makes zero progress towards

choosing a single completion candidate: it only inserts as much text

as will not narrow down things at all! But people like it for some

reason, I guess as visual feedback that what you thought the

completion candidates had in common they really do have in common. (To

be fair you can configure completion-cycle-threshold to have TAB cycle

among candidates when there aren’t many left.)

Pressing TAB a second time will pop up the *Completions* buffer, which

shows a list of all completion candidates. From there you can click on

a candidates, navigate to it and press RET, or just type some more and

press TAB again to get an updated candidate list.

Don’t knock the default completion UI. It is functional, powerful and perfectly usable out of the box. But most people want to see how the available candidates change automatically as you type. The other UIs I tried all have that feature in common; they also all have a notion of the “current completion candidate”, and there is a way to select that current candidate without finishing typing it ―usually but not always this done simply by pressing RET.

Ido

Ido also comes with Emacs and is pretty funky. For one thing it

doesn’t take over all minibuffer completion services, it only provides

special versions of certain commands, mainly to open files and switch

buffers. Those commands also enable some additional key bindings while

you are using the commands: while opening a file you can press a key

to delete a file, or while switching buffers you can press a key to

kill a buffer. This sort of thing is called “acting on a completion

candidate”, and boy do I like it ―more about this later. Ido uses

fuzzy completion, where characters only have to appear in order in a

completion candidate, not necessarily consecutively; for example epnf

matches eww-open-file.

If you like Ido but want to use it for all minibuffer completion there

are some options: there’s the ido-completing-read+ package and the

built-in fido-mode. I don’t particularly like fuzzy matching since it

feels inefficient to me, there are always two many matches for my

taste.

Helm

Helm is a comprehensive package that not only takes over all minibuffer completion duties but comes with many commands that take advantage of Helm’s additional features. It’s big and brash and opinionated. I used it for many months and was quite happy with it. I particularly liked that the Helm commands came with many actions you could perform on the completion candidates. I didn’t much like its default aesthetics or its long load time (although since you only incur that once per session it doesn’t really matter). One thing I didn’t like much is that somehow it didn’t seem to blend in very well with the rest of my Emacs experience. For example, only commands written specially to use Helm had actions for the completion candidates, and the actions had to be implemented in a particular way, you couldn’t use any old Emacs command as an action. But all in all Helm is great, an impressive piece of software that sprouted its own mini-ecosystem of related packages.

Ivy

After Helm I used Ivy and its companion Swiper and Counsel packages

for a while. It felt pretty similar to using Helm to me, except I

liked the default look of it better (which is not to say you couldn’t

easily configure the visual aspects of Helm). It also had a notion of

actions, but similarly to Helm, you needed to write them specially for

each command. I think it was less batteries-included than Helm, for

example I have a vague recollection of counsel-find-file, its

substitute for find-file, not coming with actions to rename or copy

files, which I wrote in my own configuration. It’s then that it

started to bother me that I couldn’t simply say “I want the Emacs

commands rename-file and copy-file as actions”, I was forced to write

little wrappers for them. Like Helm, I think the Ivy/Swiper/Counsel

family is great software and was a happy user. I did however, as I did

with Helm, that it reinvented the wheel too much and that something

like it would be possible that took more advantage of existing Emacs

APIs and functions.

Icomplete

This is another built-in option, which I think I only started using

after having used Helm and Ivy. I used it for a quite a while and

still think it is perfectly workable. One thing I like about it is

that, like the default completion UI, it only concerns itself with

displaying the completion candidates and leaves the important matter

of which candidates are considered to match the minibuffer input to

the current completion styles. There is no formal notion in Emacs of a

“well-behaved” completion UI, but in my head certainly such a UI

should limit itself to showing you the candidates and leave the user

to configure completion styles separately. This what I dislike about

fido-mode: it ignores your completion style configuration and makes

you use the flex completion style instead (you can change this but it

requires being sneaky, not simply setting completion-styles).

One difference between Icomplete and Helm or Ivy, is that it displays the completion candidates in a compact horizontal list like Ido, instead of one per line, like Helm or Ivy. When I was an Icomplete user, I even wrote a package called icomplete-vertical that would configure Icomplete to display the candidates vertically, one per line. Nowadays there is also a built-in package of the same name which I did not write, nor does it use my code. I remember thinking the built-in package had a bug mine lacked, triggered when you switched from horizontal to vertical during a minibuffer completion session, but I couldn’t reproduce it now so either they fixed it, or I couldn’t remember exactly what the bug was, or my memory is playing tricks on me.

live-completions

The mention of icomplete-vertical above is the start of an embarrassing parade of completion UIs I wrote myself, for myself and which I don’t think more than a handful people ever used. What marred all of my feeble attempts, other than icomplete-vertical which is just some configuration code on top of icomplete, was a distinct lack of speed. The idea of these incremental, automatic completion UIs is to show you how the candidate list changes in real time, but most of mine struggled to do this fast enough.

My live-completions package had a very simple idea: pop up the

*Completions* buffer that the default UI uses and just update it after

every key press. It let you format the completions in either a grid or

a single column, back before the default UI had the single column

view.

I think I used this for quite a while though it wasn’t very good. I believe that by the time I wrote this, I already had an initial version of Embark that took care of acting on completion candidates solving all of the complaints I had about actions in Ido, Helm or Ivy: Embark lets you use any Emacs command directly as an action, there is no need to write wrappers over existing commands; it endows every single command that has a minibuffer prompt with actions on its candidates, commands do not have to be written specially with Embark in mind to acquire actions.

grille

Another bad completion UI I wrote. Hey, at least it’s small. I don’t think I used this for very long, maybe a couple of weeks. It’s called grille because it displays completions in a grid. I have nothing else to say about it.

embark-completions

For a while Embark included its own completions UI! This is obviously a bad idea, which I only did because it was easy, since Embark had grown to have almost all the components necessary for this. It was slow, but other than that I found it surprisingly good. It was certainly featureful: it displayed the completions either one per line or in a grid, the grid optionally with zebra stripes to guide the eye. I stubbornly kept using it until I dropped it for Vertico and finally removed it from Embark.

Vertico

The excellent Vertico package is what I use now as a completion UI. The author, Daniel Mendler, and I have long worked together on a suite of packages that provide a full completion experience for Emacs. I wanted to switch from embark-completions to Vertico but held out until Daniel added a grid display to Vertico. In retrospect this was silly on my part, but I believe my stubbornness might have helped motivate Daniel to add the grid feature. Of this suite of packages, Daniel wrote Vertico, Corfu, Cape; I wrote Embark and Orderless (the latter of which we now co-maintain); and we wrote Marginalia together after noticing we were both writing something like it.

- Vertico

- a highly flexible completion UI, that can display completions one per line or in a grid, in the minibuffer or in a dedicated buffer.

- Orderless

- a highly configurable completion style, whose main

feature is matching space-separated bits of the input in any order

against the completion candidates; so

op ewwmatcheseww-open-file. - Embark

- lets you use any Emacs command as an action on any

minibuffer completion candidate or on a thing at point in a non-mini

buffer; it also comes with an extensive default configuration

assigning convenient keybindings to the most commonly used actions

(but you can always

M-xto use whatever command you want as an action!) - Marginalia

- provides extra information about completion candidates of common types, most completion UIs that display candidates as one per line will shows this extra information to the right of the candidate.

- Corfu

- this is a completion UI for completion-at-point, which I

haven’t talked about here at all ―it is the type of completion

that you get when writing code in a buffer, for example. Again here

I stubbornly held out a long time using my own contraption

(

consult-completion-in-region, which I contributed to consult). - Cape

- a suite of completion-at-point functions; again I stubbornly held out using an embark-based substitute for this for a long time ―I’m starting to notice an unflattering pattern.

Selectrum and MCT

I already finished listing the completion UIs that I actually used for

a period of time, but there are a couple of others I tried and

probably some I did not try (maybe snails, though I’m not exactly sure

what it is, since I’ve only every briefly skimmed its README). I tried

Selectrum once and, to my discredit, only complained about some minor

issues with it on reddit. At least I’m focused thematically in my

complaints: I thought it wasn’t Emacsy enough, that it disrespected

some Emacs variables it could easily respect. Well, that, and there

something I didn’t like about its completing-read-multiple experience

(I think it was that you couldn’t easily see what you had already

selected). I never used Prot’s MCT package extensively, but I would

call it similar in idea to my live-completions package, and would hope

Prot does not disagree with this characterization. It somehow seemed

smoother than my live-completions, probably because Prot had more

patience tweaking the experience than I did.

Welcome to M-x apropos Emacs

Published: .

Recently Christian Tietze called for Emacs blog posts with the topic “Take Two”, meaning things that took two or more tries to get right. He also said:

Don’t have a blog, yet?

Well, just start one already! :)

It’s the future of the internet!

I mulled over this the whole month and finally decided to start a blog about Emacs just in time to miss that first round of the Emacs carnival! (I’m likely to miss deadlines like that again in the future.)

Now, about twenty years ago, when blogs did actually seem like the future of the internet, I had one on a hosted service. I think I may have started on Blogspot, but then moved to Wordpress.com. It was a personal blog about whatever random topic I wanted to write about. I did not write very frequently on that blog, and am unlikely to write often here either, although maybe constraining the topic to Emacs might inspire me more than having no constraints did.

I was already an Emacs user back then, but I wasn’t as gung-ho about it as now, and back then I meekly accepted Wordpress making all sorts of decisions for me, which seems cowardly today; so I definitely want a more Emacsy way to write this new blog. I figure all a blog needs is a publicly accessible web page and a publicly accessible RSS feed. An important optional component is a system for comments. So, to do the easiest thing possible, I will write my blog in a single Org file (for now, I’ll manually paginate if it turns out I do keep it up!), use ox-rss to create an RSS feed, and for comments I’ll just use Mastodon.

Since I threw this together in about ten minutes, I’m sure there will be bugs. I probably don’t have permalinks correct at all.